The menace of circular debt has today become one of the gravest threats to Pakistan’s sovereignty and survival, rivaling the scourges of terrorism and insurgency that have long plagued the state.

The circular debt in the power sector has already surpassed five trillion rupees, creating a financial vortex that cripples the government, suffocates economic growth, and burdens citizens with unaffordable tariffs.

Unless Pakistan begins to think imaginatively, innovatively, and courageously, this spiraling debt will continue to erode the very foundations of the national economy.

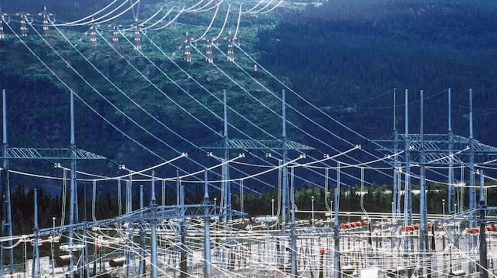

One solution, which is both viable and strategic, lies in transforming Pakistan into a regional exporter of electricity, supplying power to Afghanistan, China, and even India, thereby ensuring not only the monetization of Pakistan’s surplus energy but also the creation of a unified regional grid that could anchor stability, interdependence, and peace.

In the last two years, Pakistan, China, and Afghanistan have held multiple sessions of the Trilateral Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, yet the outcomes remain little more than scripted press releases, with no clarity about concrete achievements or actionable steps toward grid connectivity. The truth is that nobody knows whether there has been any genuine progress, for the discussions remain cloaked in diplomatic ambiguity.

What is certain, however, is that while official communiqués speak of cooperation, the ground realities tell another story. The outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) invaders from Afghanistan continue to launch deadly attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, killing soldiers and civilians alike.

The metaphor is painfully clear: Pakistan and Afghanistan are not “on the same grid.” Neither in energy nor in security do the two countries operate with alignment, and until such time as they are brought onto one common platform, both will continue to bleed—Pakistan in particular, with its soldiers’ blood flowing in the borderlands and its economy drained by the circular debt crisis.

The question then arises: how can these neighbors be brought onto one grid? This is not a rhetorical issue but a matter of national survival. The hope is that the articulation of this argument may reach policymakers who today face simultaneous challenges of insurgency, terrorism, economic fragility, and now the more insidious threat of circular debt that has begun to undermine national sovereignty more effectively than terrorism ever did.

The solution requires out-of-the-box thinking and applied strategy, but such strategies demand statesmanship and loyalty to Pakistan rather than loyalty to entrenched interest groups. To understand why this path is both necessary and feasible, it is essential to examine the current installed capacity and future electricity demand of China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In November 2014, one of us, Engineer AHA, had already written a letter to the Prime Minister of Pakistan prior to his scheduled visit to Beijing, emphasizing the need to connect Pakistan’s electricity grid with that of China. That suggestion was made in recognition of the historic ties between the two nations and the vast strategic potential of bilateral cooperation. It remains on record, and it is more relevant today than ever.

China already has an installed capacity of 3,349 GW, with over 56 percent from renewables, but this falls short of its future needs. By 2035, electricity demand will soar due to industry, transport electrification, data centers, and artificial intelligence (AI), with renewable capacity expected to double by 2030 to over 3,000 GW, still insufficient. Connecting Pakistan’s northern grid to Xinjiang could allow surplus Pakistani hydropower and renewable energy to flow into China, helping meet demand while generating revenue for Pakistan.

The Afghan case is different but equally pressing. Afghanistan generates barely 600 megawatts of electricity domestically, drawing from hydropower plants, fossil fuel stations, and some solar installations. Its demand, however, is estimated at a minimum of 5,000 megawatts, potentially rising to 7,000 megawatts as the population grows, expatriates return, and the economy finds its feet. To bridge this deficit, Afghanistan already imports more than 720 megawatts from Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, yet tellingly, not a single watt from Pakistan.

This is both a political and technical failure. If Pakistan were to supply electricity to Afghanistan, the latter could reduce dependence on Central Asia while Pakistan would gain a guaranteed external market as well cementing of relations with a neighbour sharing cultural bonds and geopolitical interests.

Such an arrangement could do more than solve energy shortages: it could bind Kabul and Islamabad into a shared economic destiny, making militancy less appealing and stability more mutually rewarding. Electricity in this sense becomes more than a commodity; it becomes a currency of peace.

Paradoxically, while Afghanistan languishes in shortage and China thirsts for energy, Pakistan itself is caught in the contradiction of abundance amid collapse. The country’s installed capacity stands at 46,605 megawatts, including a 2,813 megawatt increase from net metering.

Yet this figure is deceptive, for much of the capacity remains unused due to inefficiencies in generation, transmission, and distribution. Even more alarming is that demand is actually shrinking at a rate of 10 to 12 percent annually, as citizens revolt against unaffordable tariffs dictated by National Power & Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA), Private Power and Infrastructure Board (PPIB), and the Ministry of Power.

Nearly half of Pakistan’s electricity is consumed by domestic users, many of whom are now abandoning the grid in favour of privately financed solar systems, even if it means selling household belongings or cattle to afford the panels. In the agricultural sector, too, farmers are migrating to independent solar solutions, escaping from the state’s exploitative electricity regime. It is feared that within a year, only those engaged in outright theft will remain tied to the government’s grid, while honest consumers will exit altogether. The rapid advancement of long-life battery technology only accelerates this exodus.

Despite collapsing demand, the state continues to add more capacity. The PPIB remains committed to inducting Independent Power Producers with a combined capacity of 6,026 megawatts regardless of the consequences. Meanwhile, mega projects like the Diamer-Bhasha Dam, Mohmand Dam, Dasu Hydropower Project, and Tarbela’s Fifth Extension will add more than 12,000 megawatts in the near future.

With an existing overcapacity of nearly 35,000 megawatts, one must ask what rational plan exists for this additional power. Already burdened by 5 trillion rupees of circular debt, how much further will this overcapacity inflate the crisis? Has any government thought through this paradox? Sadly, the answer is no, and official blueprints such as Uraan Pakistan conveniently omit the terrifying implications.

It is therefore clear that Pakistan must turn surplus electricity into an export commodity. Afghanistan is an obvious buyer, China an immense market, and India—despite being an adversary—should not be ignored. India has already suspended the Indus Waters Treaty to construct hydropower projects generating 14,000 megawatts on the Western Rivers. Were Pakistan to sell electricity to India instead, it could contribute to the preservation of forests in Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, which otherwise face devastation from the construction of hydropower projects. This proposal may appear politically radical, but it is not without precedent.

India itself has built electricity connectivity with Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and is pursuing similar links with Sri Lanka. By contrast, Pakistan has failed even to connect Gwadar and Gilgit-Baltistan to its own national grid, thanks to bureaucratic inertia in National Transmission & Despatch Company (NTDC) and the Ministry of Power. If India can pursue rational interconnectivity with its neighbours, Pakistan too can consider strategic engagement, even with an adversary, for the sake of national survival.

The broader vision is unambiguous. By connecting with China, Afghanistan, and eventually even India, Pakistan can export its surplus electricity, monetize stranded capacity, stabilize its power sector, and reduce the circular debt that today threatens sovereignty itself. At the same time, such connectivity would promote economic interdependence, reduce the appeal of militancy, and turn electricity into an engine of peace and prosperity.

The alternative is grim. Without exports, Pakistan’s overcapacity will remain idle, feeding only into greater circular debt until the power sector collapses under its weight.

The urgency cannot be overstated. Circular debt today is a more dangerous enemy than terrorism, because it erodes sovereignty silently and persistently.

Terrorism may kill the body, but circular debt kills the soul of the state by weakening its financial capacity to govern. If Pakistan fails to act, the over-installed capacity of 35,000 megawatts will transform from an asset into a noose around the economy’s neck. If it acts wisely, however, it can convert this into a strength, exporting electricity to neighbors and positioning itself as the hub of a regional grid.