For better or for worse, the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt may be the most important iteration of the annual United Nations huddle since 2015 and Paris. Depending on how one sees it, COP 27 – the official abbreviation for the event with COP standing for Conference of the Parties – resulted in either the biggest win on climate since COP 15 and the Paris Agreement or represents the biggest missed opportunity.

The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan agreed at the end of the conference included a commitment by wealthy nations to provide financial reparations to developing countries that have faced the worst from ever-worsening climate change impacts. For the first time, negotiators from the Group of 77 and China (G77+China), led by Pakistan as the chair of the bloc, won an agreement to set up a ‘loss and damage fund’ to help these nations recover from the damage and economic losses wreaked from ongoing climate change impacts.

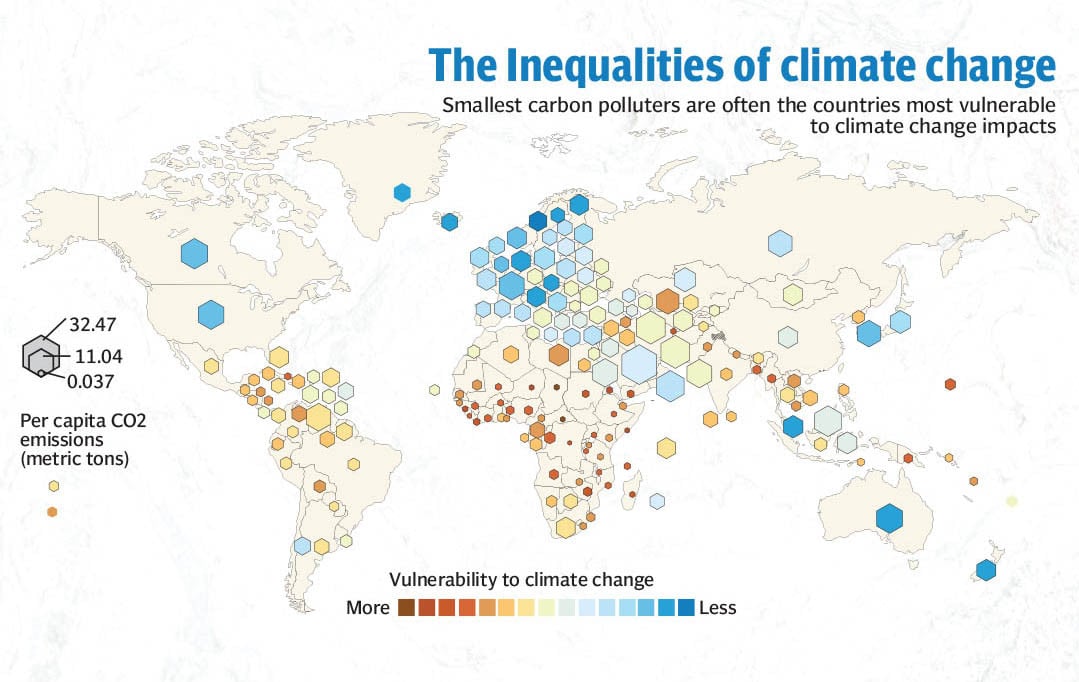

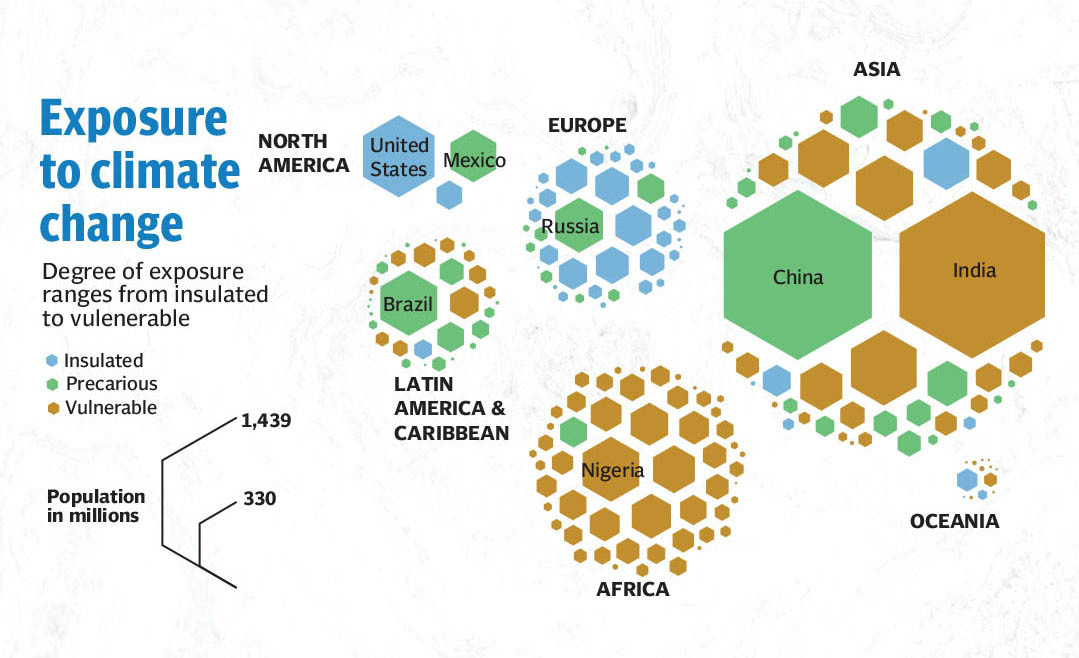

Observers and climate change activists have long pointed out that the money to help poorer nations adapt to the impacts of global warming is available. But amid the din of climate change rhetoric in the richest nations and the internal and external politics that kept meaningful progress elusive, the victims in the developing world have often found themselves invisible.

Against that backdrop, the loss and damage fund commitment has been rightfully seen as ‘historic’, ending nearly 30 years of waiting by countries that have had a minimal footprint on climate change but have faced disproportionately its devastating effects.

However, COP 27 did not result in any commitment to phase out fossil fuels, leading many leaders, activists, and scientists to express disappointment. Coming at the end of a year that saw unprecedented carnage from climate change-related disasters, like the severe floods in Pakistan, it was widely hoped that a serious commitment on fossil fuels could be reached in Sharm el-Sheikh. But no such agreement was reached despite the warning by UN chief Antonio Guterres that “humanity faces a stark choice between working together or collective suicide in the battle against global warming.”

Premature joy

Even the loss and damage fund comes with caveats that have prompted observers and experts to suggest caution. While providing some hope of recourse and assistance to nations at the forefront of climate change impacts, the agreement is neither legally binding nor is there any consensus on how such a fund, if it is ever set up, will work in practice.

Speaking to The Express Tribune, Dr Adil Najam, Dean Emeritus and Professor of International Relations and Earth and Environment at Boston University’s Frederick S Pardee School of Global Studies, suggested it was too early as yet to celebrate the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan and the loss and damage fund. “I do think that the celebrations are somewhat premature, but that does not mean that the acceptance of the fund is insignificant,” he said.

According to Dr Najam, a loss and damage fund has been a long-standing demand of the most vulnerable countries. “And its eventual acceptance – even if only in principle – is an important step forward,” he elaborated. “However, one should be clear-eyed about this: at this point there is no fund, and there is no money in such a fund.”

“What is there is the agreement to constitute a committee (the so-called ‘transitional committee’) that is supposed to come to a consensus on what such a fund might look like, how it might operate, where possible funds may come from, and how (and on whom) they may be used),” Dr Najam added. He explained that this committee is then supposed to bring these recommendations to the next COP in 2023.

“That is a tall order. Given the history of such negotiations – including the chronic habit of the polluting countries to make promises that they have no intention of keeping (such as the phantom $100 Billion that was agreed to in Paris) it would be a triumph of hope over experience that the fund will materialise any time soon,” Dr Najam warned.

But having said all of that, he stressed that the fact that the principle has been agreed means that now vulnerable developing countries have a realistic lever to keep this issue and demand alive and to keep pushing on this issue. “That is the achievement. When you are poor and vulnerable, you have to learn to celebrate even tiny steps forward. Therefore, we should celebrate this too.”

Sharing his views on topic, Dr Ashok Swain, a professor of Peace and Conflict Research at Sweden’s Uppsala University, stressed that to talk about the loss and damage fund we need to look at how the discussion on the climate crisis moved from security to justice. “Previously, the world was more concerned about security or prevention, now that discussion has shifted to justice, which means countries that bear the brunt of the crisis deserve to receive some compensation for the losses,” he said.

Dr Swain pointed that the Global South has not contributed to the climate crisis but is suffering the most. “It is a moral victory for the Global South but for all practical purposes, it doesn’t mean much. We’ve been hearing about similar climate funds since 2009, but it has never come to that level it should have been by 2020,” he shared.

According to him, much of the money that was promised for that fund, was being diverted by the West from regular development aid. “So, for this loss and damage fund, we don’t know who will provide the money, how much, and how will it be provided.”

“There can’t be any legal action against countries that don’t contribute. So, this is more of a moral victory for the South but in all practical purposes it doesn’t mean much,” he added. “I’m sorry to say that I’m not very hopeful about the Global North walking the talk in this case. The West will not provide the resources to the Global South to address their problems. We will have to live in a different world to believe that this will materialise.”

Dr Swain also noted that it is a pity that even as the world is moving towards climate justice, it is moving away from preventing climate mishaps from happening. “Leaders in the North and South are doing this to walk away from their real responsibility which is to prevent such disasters and how to address climate change,” he said. “If we don’t abide by the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit that was agreed in Paris, nothing really matters. By diverting funds from one source to the other, the West is conveniently shrugging off its responsibility, which should be lowering emissions to prevent climate change.”

Like Dr Najam and Dr Swain, the former chairperson of Karachi University’s Department of International Relations, Dr Talat Wizarat, was pessimistic about the loss and damage fund as well. “I’m not very hopeful because the United States and some of these countries that are polluting our planet more than anyone else, are very clever in wriggling out of such agreements,” she said.

“For now, they have accepted under pressure that they are causing a significant amount of pollution, but they have not made any financial commitment for this ‘voluntary’ loss and damage fund,” Dr Wizarat pointed out. “Without money, only accepting their responsibility, it should not have been announced. They should have allocated some funds, the UN should have extracted those funds from them, but the UN failed to do that, and I don’t think these countries are eager to dish out any funds,” she stressed.